Learn for the Sake of Learning

Once, a student at Pomona told me that she’d love to have a chance to think about the things she’s studying, only she doesn’t have the time. I asked her if she had ever considered not trying to get an A in every class. She looked at me as if I had made an indecent suggestion. (William Deresiewicz, author & Yale University professor)

At the beginning of this university year, when a group of student leaders were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement “grades are more important than learning,” I was shocked to see how many went to the ‘agree’ side, or at least hesitated in answering. Education — the discovery of self and the enrichment of knowledge and experience — and marks cannot be equated. Following the increasingly quantitative trend of our society’s current values, it’s hard to make a case that learning actually matters more. After all, it’s the marks that will obtain the degree, and secure a career, wealth, and respect.

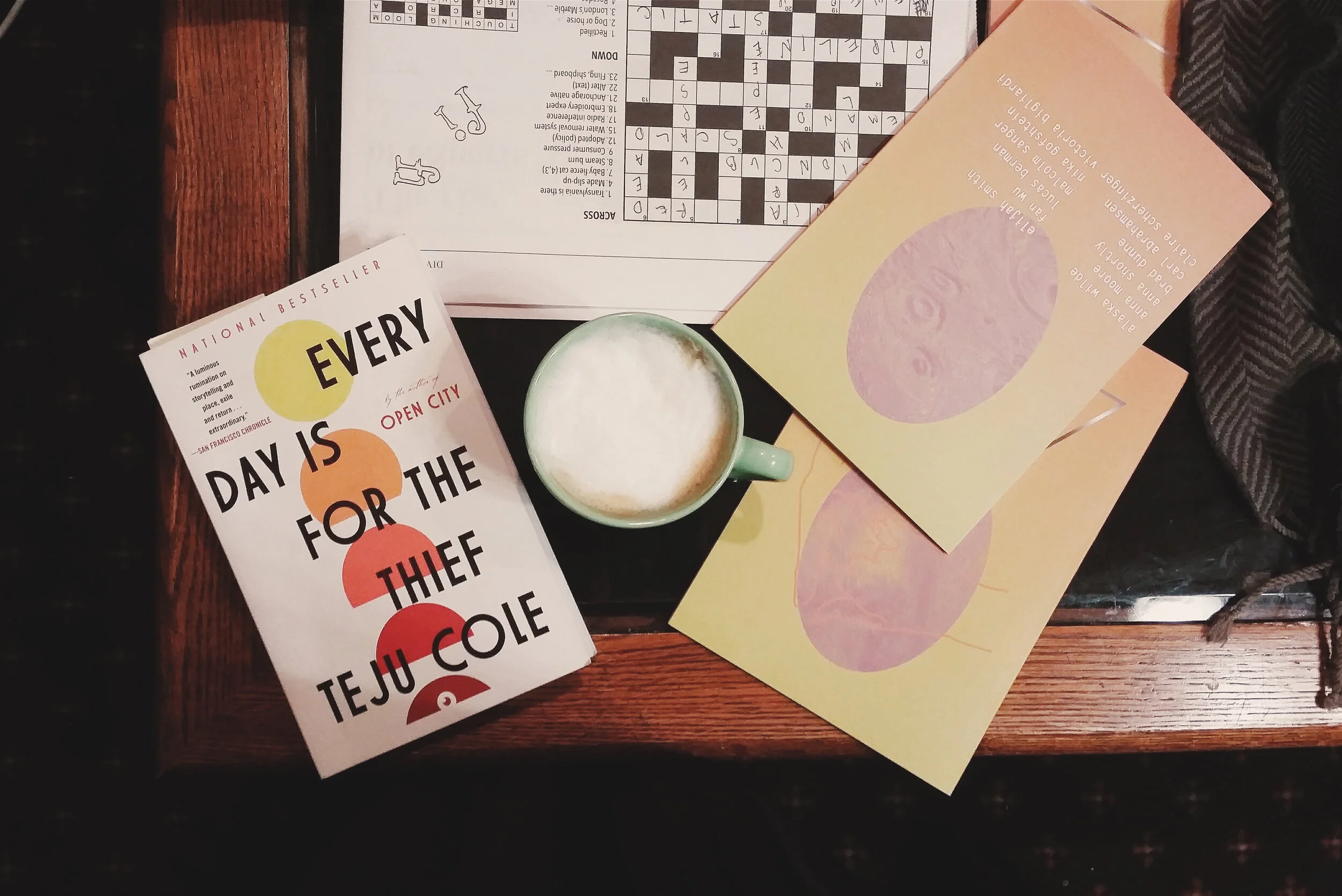

Photo: Rusaba Alam

It’s perfectly reasonable that the Pomona student in the above quotation considered Professor Deresiewicz’s proposal to be an “indecent suggestion” because students pay thousands every year to go to university, and we have no choice but to succeed by their (often questionable) standards. With intensely hefty course-loads packed into 24 – 72 hours of lecture a year, it’s difficult to absorb all the information as thoroughly as we’d want to. How ironic (and frustrating) is it that the structure of education so often prevents us from actually learning? As fascinating as my readings this year are (and I truly want to finish all of them), it’s impossible to get through and enjoy the multiple novels assigned a week before we jump on to the next. Sometimes it’s necessary to skip over all the nuances of an issue in an effort to quickly regurgitate knowledge in the next test or essay.

This past summer, I studied French at the University of Québec à Trois-Rivières, through the Explore program. Although it was for credit, the program structure was somewhere between a course and a summer camp. What struck me most about it was that I learned about the same amount of French there, in five weeks, as in the past six years I’d spent in the immersion program, and arguably more.

The program’s month-long curriculum included projects like mock trials, mock job interviews, speed dating, debates, board and card games such as Taboo, and a ton of discussion in French to help build vocabulary and speech. This liberty isn’t allowed or encouraged in school regularly for one reason: it’s more difficult to evaluate. Without such strict limits and expectations on marks, there was more room to practice, focus on nuances and details of oral French, and truly improve. I looked forward to going to my conversation workshop every day, where we would actually be speaking in French all period, through skits and scenarios, discussion topics, and games. Of course, there were the hours of evaluated grammar sheets too, but it wasn’t the only part of learning. My confidence with the language developed immensely in those five weeks. I grew to love the language again — something I’d almost forgotten during my time in immersion.

As Kourosh Houshmand, a Top 20 under 20 student at the University of Toronto, said:

It was an incredible experience learning [that the] day that I was doing [better] at school, the less I knew about current issues. And vice versa, when I know a lot about everything else I do terribly at school.

Photo: Rusaba Alam

There are so many more important parts to school than our grades, and in prioritizing the latter, we forsake good education and experience. At the University of Toronto, although over a thousand extra-curricular activities are advertised, it saddens me how many cannot participate for fear of distracting from their studies. That is not all learning is and it’s definitely not the most valuable experience offered on campus.

As a straight-A student who has always been very focused on good grades, I found myself at a bit of crossroad when I realized this month that I did not have the time to continue with all my extra-curriculars and complete all my required readings at the same time. As much as the reasonable solution would’ve been to drop some activities, I couldn’t do it. Running my café, writing, and working to form communities for people who feel as lost as I did last year, are the happiest and most fulfilling parts of my student life. It’s when I feel like I have a purpose, I’m moving forward, truly making a difference.

As Yale Professor Deresiewicz noted:

Our system of elite education manufactures young people who are smart and talented and driven, yes, but also anxious, timid, and lost, with little intellectual curiosity and a stunted sense of purpose: trapped in a bubble of privilege, heading meekly in the same direction, great at what they’re doing but with no idea why they’re doing it.

I don’t remember my exact average in high school, but I do remember every extra-curricular experience I had, and how they shaped me in powerful ways. I do remember the most important material from my classes and readings, the fascinating ideas that help build my mind and character, even if I didn’t get an A on that midterm essay. At the end of the day, I love to learn above all and I strongly believe that that should always remain the priority of living.