Little Girls' Dreams

My first Halloween, when my family moved to New York when I was 6, I wanted to dress up as a fairy princess. My favourite colour at the time was pink. I dreamed of having flowing hair, wearing beautiful dresses, and marrying the man of my dreams in a castle.

For a long time, I looked down on that version of little me. My priorities have changed: marriage is no longer my measure of success, and physical beauty no longer a factor in judging character. All that seems self-explanatory, but something still didn’t sit right.

I couldn’t pinpoint what it was until I began taking a closer look at Sansa Stark’s character in Game of Thrones. As I wrote last week, many fans continue to dislike her, particularly in comparison to the female characters who can handle themselves on a battlefield, such as Arya Stark or Brienne of Tarth. What I want to focus on now though aren’t those viewers but the ones who love her in the later seasons, who praise her character development by comparing her to the girl she was.

“I’m stupid. A stupid little girl, with stupid dreams, who never learns,” Sansa says at 14 years old. I’ve seen this quotation highlighted many times to describe the person she was then. As one fan stated, “I don’t think anyone has given as good an assessment of Sansa as she did herself.” And another: “Sansa may have been a stupid little girl with stupid dreams, but now she’s a wolf slaughtering everyone who harmed her.”

However, let’s take a closer look at those “stupid dreams.” In season 1, Ned Stark tells Arya, “You will marry a high lord and rule his castle, and your sons shall be knights, and princes, and lords.”

Presumably, he has been telling Sansa the same thing all her life (likely more often, as Sansa is the eldest daughter and described as more conventionally attractive), and he wouldn’t have been the only one. Is it a bad thing then that little girls grow up dreaming the dreams they’re taught to?

The counter to this point could well be that Arya never wanted that. As she tells her father, “that’s not me.” As she tells Tywin Lannister, “most girls are idiots.” While it’s great that Arya has other interests, praising her choices over Sansa’s brings us into the same problem as using “you’re not like other girls” as a compliment: what exactly is wrong with other girls and why is it a good thing to be unlike them?

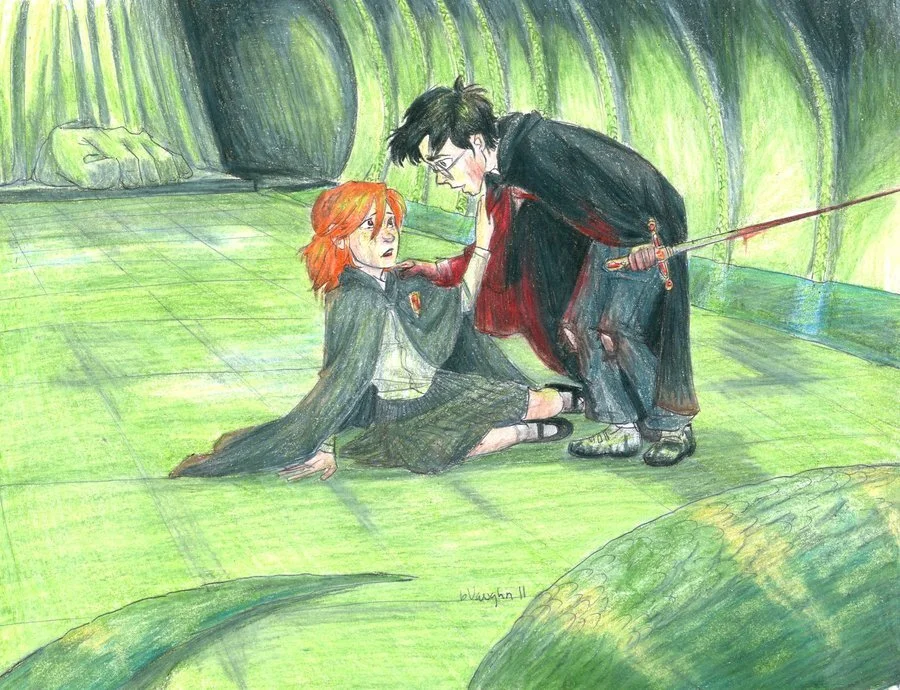

A similar point can be made with another one of my favourite fictional characters: Ginny Weasley. Before bursting into the scene at 14 as a strong, confident, brave, and smart heroine, she was a shy and awkward preteen with a crush. As with Sansa, fans praise her character development often without acknowledging that 10-year-old Ginny is not only an average girl of her age — but also that’s how we as a society condition our girls to be.

Audiences tend to like the girls who reject those “stupid dreams” from the start — Katniss Everdeen, Hermione Granger, Arya, and Brienne. This mindset is problematic for several reasons.

The first is obvious, and one I’ve addressed before: traditionally masculine values, interests, and qualities are considered superior to feminine ones, which leads to sexist definitions of strength and success — a point Virginia Woolf made 90 years ago in A Room of One’s Own. So far, I’ve noticed little progress in pop culture of questioning those actual definitions. Why are rom coms still considered trivial while action films lauded? Why is liking sports seen as cool but liking fashion seen as flimsy? Why is a pantsuit viewed as professional while a sparkly dress is not?

Disregarding preteen girls — their dreams, their feelings, their behaviours — also fails to place the responsibility on how we as a society raise our children and instead blames individual women for their so-called stupidity or naivety. We compliment girls for their beauty, then call them shallow when they grow up valuing it. We feed them marriage as a centrepiece of “happily ever after” but congratulate them for thinking otherwise. Is it fair to hold a child to that standard? To only praise them once they manage to see through the ruse?

Another point worth noting is that this narrative in pop culture often presents female strength arising as a result of violence and pain. Brienne was bullied, and thus, she became a knight. Katniss grew up in poverty, and thus, she learned to fend for herself. Ginny was kidnapped and nearly killed, and only afterwards does she come back a smart and skilled fighter. Sansa was psychologically tortured and raped, and only then did she learn.

The moments of strength before, if any exist, are usually overlooked: Ginny standing up to Draco at Flourish and Blotts and breaking into the broomshed to teach herself to fly; Sansa defending Lady, and all her mocking comments to Joffrey in court. These girls were always strong, but we only ever saw them scrambling in a new and dangerous environment before they were beaten to the ground. What would it have looked like to see them grow without trauma?

This isn’t to say that those stories aren’t valid, but I wish I could point to more examples of strong female character development that weren’t shaped by rejection of traditional femininity or rejection of girlhood prior to trauma. Elle Woods from Legally Blonde is actually one such example — a woman who grew and learned without needing to throw away her love for pink, fashion, or manicures.

The points I make are not so we can judge these women for who had it tougher, who was smarter or braver, or who took more chances first. In the end, they’re fictional, but the ways we judge them are the same ways in which we judge our girls and women. Certainly, we should praise Arya’s courage, and Katniss’s strength, and the Queen Sansa grew to be — but we should also look kinder upon 10-year-old Ginny speechless in front of a famous boy she likes, 13-year-old Sansa lost in the politics of a malicious court at war, and all the little girls who have to learn and unlearn what and how to dream.

It is impossible, particularly for women, to grow without criticism. Double standards lie everywhere, and I am done rejecting 6-year-old me and all the girls who dreamt of riding off in the sunset with the love of their life. I watched soap operas with my grandmother every night at that age. She told me her highest hope was to see me as a model on TV. I wasn’t stupid to want the dreams I was fed, which also says a lot about the power of our words in influencing the choices girls pursue later on.

Now, at 24, I dream of many, many things — but frankly, flowing hair, beautiful dresses, and marrying the person of my dreams in a castle doesn’t sound too bad. And that’s not stupid either.