Villains, Fighting, and the Reduction of Complex Stories

I want to say I’m writing this post after watching the Avatar: The Last Airbender live action show, but the truth is I could not get through the first episode. I made it about forty minutes in. The visuals were pretty and the fight scenes dramatic; it’s just that the story didn’t mean anything anymore.

I was baffled (though not surprised, given how the original show’s creators left the Netflix project due to “creative differences” ) that so-called storytellers heading these large budget production companies have no idea what makes a good story. The heart of ATLA is its spirituality, joyfulness, and creative approaches to world building that say something different about our world. Through elements of fantasy, it addresses questions like what conflict resolution looks like if not killing, or what is considered disability versus strength. To use Ursula K. Le Guin’s words, it is fundamentally a story that holds.

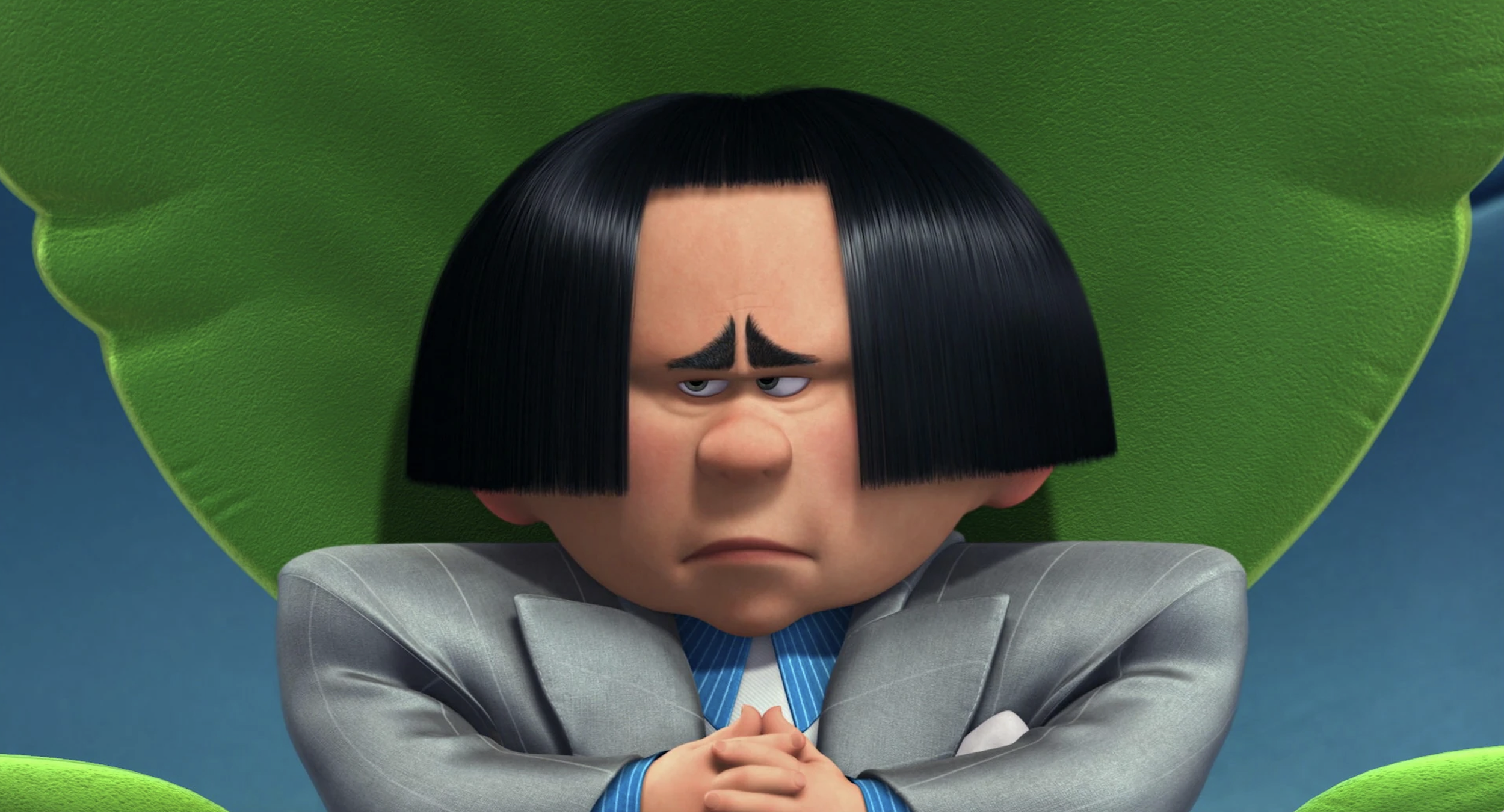

Credit: madiswanrh, based on Nickelodeon

This is not to say that the original ATLA is devoid of conflict, but rather that it is one component among many in a story that addresses internal, interpersonal, and global struggles not only through fighting but also through reflections on balance, sacrifice, and love. As Le Guin wrote in “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”:

One relationship among elements in [a story] may well be that of conflict, but the reduction of narrative to conflict is absurd. (I have read a how-to-write manual that said, "A story should be seen as a battle," and went on about strategies, attacks, victory, etc.) Conflict, competition, stress, struggle, etc., within the narrative conceived as carrier bag/belly/box/house/medicine bundle, may be seen as necessary elements of a whole which itself cannot be characterized either as conflict or as harmony, since its purpose is neither resolution nor stasis but continuing process.

The ATLA live action show reduced the story to its fight scenes in several ways: firstly, with a violent opening that established a ruthless tone off the bat. The destruction of the air temples was not shown for the impact that it had on Aang (to foreground grief) but became another way to establish fire nation = bad guy, flattening the development for our main characters.

On that note, everyone has now become so serious!* What does it say about shared values to associate serious/grumpy with adult, and happy/funny with immaturity? Capitalism is so good at relegating joy and pleasure to tiny specific safe sites in our life; depictions of these priorities in mainstream media only reinforce what is worthwhile to show. Conflict is serious, so we are not going to ride elephant koi or go penguin sledding or jump through clouds or any of the insignificant pastimes that make up the fabric of relationality and being. We don’t have time for all that (we have to work).

Showrunners have explicitly compared the live action adaptation to Game of Thrones, stating that they hope to cater to more “mature” audiences, because the show cannot “just be for kids”, which misses the point entirely since this show has never been solely loved by kids. Good stories for children will always appeal to everyone, because we all recognize that part within ourselves.

The impulse to make things more mature creates more stories about fighting, which then reflect back upon children’s television in a recursive loop. It’s like Hollywood does not know how to tell stories without a bad guy. Someone always has to be the bad guy.

I remember how disappointed I was to see a genre-breaking depiction of grief in WandaVision only to have it collapse in the last two episodes by the introduction of a bad guy that needs fighting. Similarly for animated movies like Zootopia or The Lorax—particularly if the point is to address complex topics like racism and environmental sustainability (which these stories try to)—naming an obvious villain is a textbook way to make viewers comfortable and thus deflect blame. It couldn’t possibly be my role to address micro-aggressions, because it was the evil sheep’s fault! The Lorax’s Hollywood transformation is especially frustrating given that the source material was so strong to start with: the narrator/villain of that children’s picture book, the Oncler, is never depicted. We never see their face, because the point is that the Oncler could be anyone.

Perpetuating the same narratives of conflict in mass media not only dictates a cultural hierarchy of what is considered important (back to Virginia Woolf) but also creates distance in how we are able to see ourselves represented in stories at large. Where is the point of emotional connection if ATLA is just about bending and war? Cool animations will never be enough to replace meaning, and viewers will continue to feel unimpressed, detached, even without identifying exactly why.

*Aang’s live action ability to fly without a glider is also an erasure of existing internal conflict from the original show: that between being tethered to earthly desires and achieving spiritual transcendence. In season 3 of The Legend of Korra, an Airbender devotes years of studying to this art and is only able to achieve unassisted flight when his lover dies (thus removing his last earthly tether). Aang, in being unable to let go of Katara, is never able to achieve this power. #notserious #kidshow